Something more than Sexual:

Gender and Pop Art

Sex sells, that’s the problem. Image is everything. The media feeds us these conceits – the boy next door and the housewife at the kitchen table.

You watch. You buy. You lick your lips. In this world of commercialism, pop art pitches itself. But questions arise when we look to these ascribed roles of gender. Sheffield has recently had a pop at celebration with It Moves Forward, a retrospective of the works of Richard Hamilton until 26 October 2019 at Graves Gallery, as well as the work of Sir Peter Blake recently at Kommune. In pop art the role of women is often glamorous, sexualised and powerful, but do we risk creating an unattainable distortion? Does the move to create an image of beauty alienate it from the truth?

I’m going to talk about Marilyn Monroe. Visually arresting as she was, her image became one repeated by pop artists, exuding glamour and delicious camp. Through my eyes, this motif is one of playful adoration. She’s portrayed as a woman of unashamed femininity. Does this bely a harsh reality of the viewer being a voyeur? Each of us are afford a view from any angle we want.

In Richard Hamilton’s ‘My Marilyn’ we see the self-censorship and consideration she had regarding her image. The paparazzi are her constant companion, and her vulnerability is displayed as a statement. These are a series of non-consenting images. I felt uncomfortable, as if witnessing a violation. Another of Hamilton’s images that instilled the feeling of unease while walking around the Graves was ‘Picasso’s Meninas’, a study after Picasso’s ‘Las Meninas’ which was itself inspired by Velázquez. We see how the female form was venerated – the relationship between artist and muse is one that is fraught with danger.

I make no apologies for my dislike of Picasso’s habit of luring young women to his studio to create his work. He influenced them to engage in sexual affairs under the guise of inspiration. This is made no more prevalent than in 1932’s ‘Le Rêve’, a painting which shows the artist’s penis resting on his model’s face. I’m no prude, but the question of consent and the assertion of male dominance is never far from view.

Hamilton’s works regularly reference cubism and dadaism. Among the earlier works in the Graves exhibition are ‘Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?’ and ‘Interior’. Sketches for these paintings are also displayed, showing their formation and Hamilton’s early workings in a nod to Duchamp. In the former we see male and female figures surrounded by scenes of domestic bliss, in the latter, a solitary woman surrounded by the trappings of the modern home. Like the pages of a catalogue, the image anaesthetises the viewer to the media objectification of body image. Man with his chiselled physique standing proud, woman luxuriating on the sofa. All eyes on them.

But this can’t be the only fight women have in the world of pop art. It is to Rosalind Drexler that we turn for a contemporaneous commentary on male power and the oppression of women. In Hamilton’s work, we see woman as either an object of desire or an accessory. With Drexler, the women are enraged. Drawn to a place of desperation. Born and raised in The Bronx during the years of Great Depression, her works resonate with an unquiet pace. Motion is caught in an instantaneous intake of breath before the main event.

Stress. Anxiety. Life. Death.

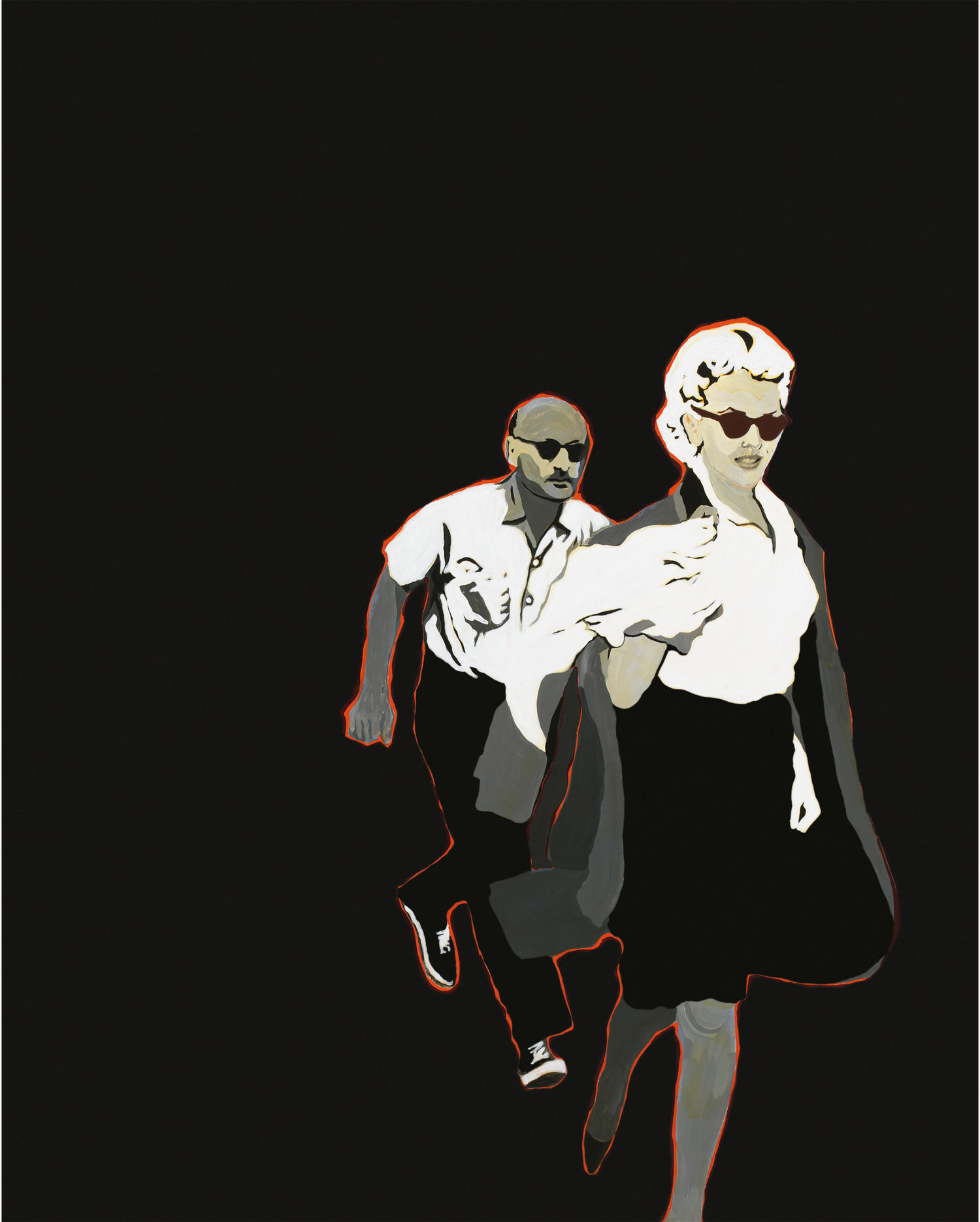

And yes, Drexler created a Marilyn, but this one speaks to the very thing we are still obsessed with today: invasion of privacy and the celebrity as a universal commodity. In 1963’s ‘Marilyn Pursued by Death’, the paparazzi are seen for the harm they cause and, ultimately, the pain they inflicted on Monroe. A voracious predator lusting after its latest victim is seen lurking in the shadowy darkness. Marilyn flees from the edge of the scene in terror. The energy of the piece shouts at you through the frame. In much the same way as Hamilton’s ‘My Marilyn’, we feel a sense of violation. But unlike Hamilton’s Marilyn, the focus is shifted towards the cause of the hurt. We know the villain behind the flash.

And so to Peter Blake. Through his Marilyn, we see the creation of a new religious idol. The painting ‘Marilyn Monroe, Black’ is adorned with diamonds and ensconced in the colour of the gods, with a clear separation of us from the holy of holies. To look upon it is to worship at the new altar to beauty, celebrity and fame. But in this image we see the nature of that celebrity as symbiosis. An uneasy peace. The dark black of the piece, rather than heightening the tension of Drexler’s Marilyn, gives us a sense of the beyond. A collective space of reflection. A meditative state in which to view our icon.

Our interpretation of these artworks through the lens of a more enlightened and balanced view of gender, sexual liberation and consent must be met with an understanding of the circumstances around their creation. Often a retrospective merely displays the work and adds no new narrative. Here, sadly, is where the exhibitions at both Graves and Kommune have failed. It is incumbent on us to challenge ideals, recognise the practices that cause misogyny and bring about discussion.